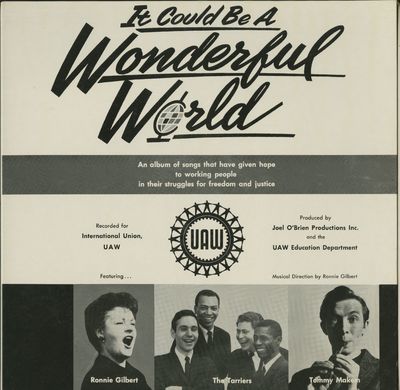

It Could be a Wonderful World

It Could Be a Wonderful World: An album of songs that have given hope to working people in their struggle for freedom and justice

It Could Be a Wonderful World was produced for the International Union, UAW. Music featuring:

- Ronnie Gilbert

- The Tarriers

- Tommy Makem

- Clarence Cooper

JOE HILL

Sung on Side One by Clarence Cooper;

on Side Two by Ronnie Gilbert

1. I dreamed I saw Joe Hill last night

Alive as you and me.

Says I, "But Joe, you're ten years dead."

"I never died," says he.

"I never died," says he.

2. "In Salt Lake, Joe, by God," says I,

Him standing by my bed,

"They framed you on a murder charge."

Says Joe, "But I ain't dead."

Says Joe, "But I ain't dead."

3. "The copper bosses killed you, Joe,

They shoe you, Joe," says I.

"Takes more than guns to kill a man,"

Says Joe, "I didn't die."

Says Joe, "I didn't die."

4. And standing there as big as life

And smiling with his eyes,

Says Joe, "What they forgot to kill

Went on to organize.

Went on to organize."

5. "Joe Hill ain't dead ," he says to me,

"Joe Hill ain't never died.

Where working men are out on strike

Joe Hill is at their side.

Joe Hill is at their side."

6. "From San Diego up to Maine

ln every mine and mill,

Where workers strike and organize,

It's there you 'll find Joe Hill

It's there you'll find Joe Hill."

7. I dreamed I saw Joe Hill last night

Alive as you and me

Says I, "But Joe, you're ten years dead."

"I never died," says he.

"I never died," says he.

In 1901, a young Swede, Joel Emanuel Hagglund, emigrated to the United States at the age of nineteen. He worked at odd jobs, mined copper, worked on the docks of California, shipped out as a sailor on the Honolulu run, and worked in the wheat fields. He changed his name to Joe Hill somewhere along the line and joined the Industrial Workers of the World, the IWW or Wobblies, in 1910. A militant industrial unionist, he was always "scribbling" songs, some of which became labor classics, like "Casey Jones-the Union Scab," and "The Preacher and the Slave." He was arrested on a murder charge in Salt Lake City, and despite vigorous protests by the American Federation of Labor, workers throughout the world, the Swedish government, and the intervention of President Woodrow Wilson, was shot by a five-man firing squad on November 19, 1915. The day before his execution, he wired Wobbly leader Big Bill Haywood, "Don't waste time mourning. Organize." The night before he was shot, a speaker at a protest meeting in Salt Lake City cried: "Joe Hill will never die!" This moving song by Earl Robinson and Alfred Hayes, written twenty years after his death, helps keep his memory alive as a symbol of all those killed while struggling for labor's rights.

SOLIDARITY FOREVER

l. When the union's inspiration through the workers' blood

shall run,

There can be no power greater anywhere beneath the sun.

Yet what force on earth is weaker than the feeble strength

of one?

But the union makes us strong.

CHORUS: Solidarity forever!

Solidarity forever!

Solidarity forever!

For the union makes us strong.

2. They have taken millions from us that they never coiled to

earn,

But without our brain and muscle not a single wheel could

turn.

We can break their haughty power, gain our freedom while

we learn

That the union makes us strong.

3. In our hands is placed a power greater than their hoarded

gold,

Greater than the might of armies magnified a thousand fold.

We can bring co birth a new world from the ashes of the

old,

For the union makes us strong.

This is the most popular union song in America. Written in 1915 by poet Ralph Chaplin, an organizer for the Industrial Workers of the World, the idea came to him while helping coal miners in the Kanawha Valley strike in West Virginia. His defiant, militant lyrics combined with the stirring march rhythm of the Civil War tune, "The Battle Hymn of the Republic," have made this song the anthem of the American labor movement and a favorite on picket lines and at union meetings throughout the nation.

NO IRISH NEED APPLY

Sung by Tommy Makem

l. rm a decent boy just landed from the town of Ballyfad ;

I want a situation and I want it very bad.

I have seen employment advertised, "It's just the thing,"

says I,

But the dirty spalpeen ended with "No Irish need apply."

"Ha," says I, "that is an insult, but to get the place I'll cry,"

So I went to see the blackguard with his "No Irish need

apply."

Some do think it a misfortune to be christened Pat or Dan,

Bue co me it is an honor to be born an Irishman.

2. Well, I started out to find the house; I got there mighty soon.

I found the old chap seated ; he was reading the Tribune.

I told him what I came for, when he in a rage did fly.

"No!" he says, "You are a Paddy, and no Irish need apply."

Then I gets my dander rising, and I'd like co black his eye

For co cell an Irish gentleman "No Irish need apply."

3. I couldn't stand it longer so a-hold of him I took,

And I gave such a beating as he'd get at Donnybrook.

He hollered "Milia Muether," and co get away did cry,

And he swore he'd never write again "No Irish Need

Apply."

Well, he made a big apology; I told him then goodbye,

Saying, "When next you want a beating, write 'No Irish

Need Apply.'"

America has long been the Golden Land of opportunity to millions of poverty-stricken immigrants, who were eagerly recruited to fill the insatiable maws of a growing economic system. Frequently. however, the economic machine creaked and went into a depression. Then the immigrants who came looking for work found themselves low man on the totem pole. Their color, nationality or religion were used co bar them from jobs. The barrier of discrimination has been used in this country at various times against Irish, Jews, Poles, Chinese, Italians and many others. In recent years, those hardest hit have been Negroes and Latin Americans. This song stems from the time of the Irish potato famines of 1845-47 when thousands of Irishmen fled their starving country. In America, signs were soon posted, "No Irish Need Apply," and chis song was written to express the resentment of Irish workers and their militancy, which is not unlike the militancy of the young people in the sit-in and integration movements today.

THE MILL WAS MADE OF MARBLE

Sung by Ronnie Gilbert and Marshall Brickman

CHORUS: The mill was made of marble,

The machines were made of gold,

And nobody ever got tired,

And nobody ever grew old.

l. I dreamed that I had died

And gone to my reward-

A job in Heaven's textile plane

On a golden boulevard.

2. This mill was built in a garden—

No dust or lint could be found.

The air was so fresh and so fragrant

With flowers and trees all around.

3. There was no unemployment in heaven;

We worked steady all through the year;

We always had food for the children;

We never were haunted by fear.

4. When I woke from this dream about heaven

I wondered if some day there'd be

A mill here on earth like the one up above

For workers like you and like me.

In 1947, textile workers in North Carolina lose a five-month strike for a sixty-five cents an hour minimum wage at the Safie Textile Mill. Before it ended, an old striker brought Margaret (Pat) Knight of the union staff a tatte1ed sheet of paper with eight lines about a "mill built of marble." When she showed the words to Joe Glazer, he reworked it, added several verses and, with Pat Knight, set it to music. Though written in 1947, the song symbolizes the heartbreak of workers in an industry with a 150-year-long, unhappy history of low wages, long hours, child labor, stretch out and speed-up, and company-dominated mill towns.

ROLL THE UNION ON

CHORUS : We're gonna roll, we're gonna roll,

We're gonna roll the union on!

We're gonna roll, we're gonna roll,

We're gonna roll the union on!

l. If the boss is in the way we're gonna roll right over him,

We're gonna roll right over him, we're gonna roll right over

him.

If the boss is in the way we're gonna roll right over him;

We' re gonna roll the union on!

2. If the scab is in the way we're gonna roll right over him,

We're gonna roll right over him, we're gonna roll right over

him.

If the scab is in the way we're gonna roll right over him;

We're gonna roll the union on!

3. If the sheriffs in the way we're gonna roll right over him,

We' re gonna roll right over him, we're gonna roll right over

him.

If the sheriff's in the way we're gonna roll right over him,

We're gonna roll the union on!

Written at an Arkansas labor school in 1936, this song soon became popular with the Southern Tenant Farmers' Union. A Negro sharecropper and union organizer, John Handcox, wrote the first verse, and Lee Hays added ochers. Based on a gospel hymn, "Roll the Chariot On," the unionise merely substituted "boss" for "Devil" and "union" for "chariot" and another labor hit was on its way. The song became very popular and was the favorite of Alan Haywood, the CIO's chief organizer, who died in 1953.

WHICH SIDE ARE YOU ON?

1. Come all of you good workers,

Good news to you I'll cell

Of how the good old union

Has come in here co dwell.

2. My daddy was a miner

And I'm a miner's son,

And I'll stick with the union

Till ev'ry barrle's won.

CHORUS: Tell me, which side are you on?

Which side are you on?

Which side are you on?

Which side are you on?

3. They say in Harlan County

There are no neutrals there;

You'll either be a union man

Or a thug for J. H. Blair.

4. Oh, workers, can you stand it?

Ob, tell me how you can.

Will you be a lousy scab

Or will you be a man?

5. Don't scab for the bosses,

Don't listen to their lies.

Us poor folks haven't got a chance

Unless we organize.

In 1931, Harlan County, Kentucky coal miners were on strike. Mountaineer miners fought back hard against armed company deputies who beat, shot and killed union leaders. During the strike, Sheriff J. H. Blair came to the home of union leader Sam Reece while his wife, Florence, was there with their seven children. Failing to find Sam, the sheriff's force kept watch outside, ready to shoot Sam if he returned. This incident inspired Mrs. Reece to write the words to this song, which has since been adapted by workers for use in many other strikes. It dramatized the kind of class war that existed in America in the depression years.

WE SHALL NOT BE MOVED

1. The union is behind us; we shall not be moved.

The union is behind us; we shall not be moved.

Just like a tree standing by the water,

We shall not be moved.

CHORUS: We shall not be, we shall not be moved.

We shall not be, we shall not be moved.

Just like a tree standing by the water,

We shall not be moved.

2. We're fighting for our freedom; we shall not be moved.

We're fighting for our freedom; we shall not be moved.

Just like a tree standing by the water,

We shall not be moved.

3. We're fighting for our children; we shall not be moved.

We're fighting for our children; we shall not be moved.

Just like a tree standing by the water,

We shall not be moved.

4. We'll build a mighty union; we shall not be moved.

We’ll build a mighty union; we shall not be moved.

Just like a tree standing by the water,

We shall not be moved.

During a strike of the West Virginia Mine Workers Union in 1931, 106 families living in company homes were evicted one morning. The League for Industrial Democracy and Brookwood Labor College were conducting a Labor Chautauqua for the union, and Mrs. Ethel Clyde, a philanthropist who had given the L.I.D. money for its educational work among the miners, was shocked at the sight of the miners and their children sleeping in an open field, without even tents to shelter them. She put up money for rent so that the miners could get back into their homes. That night, jubilation reigned supreme. A choir of Negro union members started to sing new verses to an old hymn, "We Shall Not Be Moved." They started out with: "The people of New York have decided-We shall not be moved. "Just like a tree that's planted by the water, We shall not be moved." Other verses included: "They're fixin' to take our children but we shall not be moved. "They're movin' out our furniture but we shall not be moved." The song is a great picket line favorite because it is easy to add new verses telling the story of any particular strike.

SIT DOWN!

1. When they tie a can

To a union man,

Sit down! Sit down!

When they give'm the sack,

They'll rake him back,

Sit down! Sit down!

CHORUS: Sit down, just rake a sear,

Sit down, and rest your feet,

Sit down, you've got 'em bear,

Sit down! Sit down!

2. When they smile and say,

"No raise in pay",

Sit down! Sir down!

When you wane the boss

To come across,

Sit down! Sir down!

3. When the speed-up comes,

Just twiddle your thumbs,

Sit down! Sit down!

When you wane 'em co know

They'd better go slow,

Sit down! Sit down!

4. When the boss won't talk,

Don’t take a walk,

Sir down! Sir down!

When the boss sees that,

He'll want a chat;

Sit down! Sit down!

In 1936 and 1937, General Motors' strikers developed one of labor's most dramatic weapons in the struggle for industrial organization-the sit-down strike. Auto workers laid down their tools, but instead of going out on strike, physically took possession of the plant to prevent the company from moving equipment to another factory or moving in scabs-either of which developments might well have broken the strike. The GM sit-downs led a veritable wave of organizing strikes and sparked the growth not only of the Congress of Industrial Organizations but of many American Federation of Labor unions as well. During the auto sitdowns, the United Auto Workers union maintained excellent discipline in the plants, sanitary squads kept them spic and span, and the union carried on educational classes and organized choruses and bands.

IT COULD BE A WONDERFUL WORLD

1. If each little kid could have fresh milk each day,

If each working man had enough rime to play,

If each homeless soul had a good place to stay,

It could be a wonderful world.

CHORUS: If we could consider each other

A neighbor, a friend, or a brother,

It could be a wonderful, wonderful world,

It could be a wonderful world.

2. If there were no poor and the rich were content,

If strangers were welcome wherever they went,

If each of us knew what true brotherhood meant,

It could be a wonderful world.

Union men and women are particularly fond of this song because it expresses in clear and simple terms the essential goals and philosophy of the labor movement. While labor's aims are frequently stated in economic terms, basic to them has always been the biblical concept that "I am my brother's keeper." That is why unions in America pioneered in publishing for free public education and why they back higher minimum wages today, even though those minimum wages would benefit primarily nonunion workers since most union members get higher wages. This song was written by Hy Zaret and Lou Singer in 1947 as part of a group of "Little Songs on Big Subjects." Originally commissioned as public service spot announcements for radio station WNEW in New York City, the songs caught listeners' fancies, and were soon played over more than 500 radio stations throughout our land.

UAW-CIO

1. I was standing round a defense town one day

When I thought I overheard a soldier say:

"Ev'ry tank in our camp has that UAW scamp,

And I'm UAW too, I'm proud to say."

CHORUS: It's the UA W-CIO, makes the army roll and go;

Turning out the jeeps and tanks and airplanes ev'ry

day.

It's the UAW-CIO, makes the army roll and go,

Puts wheels on the U. S. A.

2. I was there when the union came to town;

1 was there when old Henry Ford went down;

I was standing by Gate Four when I heard the people roar,

"They ain't gonna kick the autoworkers around."

3. I was there on that cold December day

When we heard about Pearl Harbor far away;

I was down in Cadillac Square when the Union rallied there

To put those plans for pleasure cars away.

4. There'll be a union label in Berlin

When those union boys in uniform march in;

And rolling in the ranks there'll be UAW tanks:

Roll Hitler out and roll the union in.

Author John Gunther has called the United Auto Workers, now part of the AFL-CIO, "the most volcanic union in the country." With more than a million members, it has pioneered in such collective bargaining fields as pensions, cost-of-living increases, supplemental unemployment benefits (SUB), and regular productivity wage increases. Before America entered World War II, Walter Reuther proposed a dramatic plan to convert the auto plants to produce 500 planes a·day a plan ridiculed by the industry. In a short time, Reuther's basic concept was adopted and production zoomed to 100,000 planes a year. During the war, UAW members (and unionists in steel, rubber, glass, electrical and scores of other industries) mass-produced armadas of planes, jeeps and tanks which rolled the war on to victory against the Nazis and their allies. This song was written by Bess and Baldwin Hawes.

SONG OF THE GUARANTEED WAGE

1. I'll tell you the story of Jonathan Tweed,

Who had a good wife and four children to feed.

His wages bought food and a place they could bunk,

But during a layoff, poor Johnny was sunk.

Yes, but during a layoff, poor Johnny was sunk.

2. When Johnny was working he'd get along fine

But when he was laid off he'd worry and pine.

He did not get paid, but his bills did not cease,

No wonder poor Johnny could not sleep in peace.

No wonder poor Johnny could not sleep in peace.

3. Now, Jonathan Tweed said there must be a way

To guarantee workers a regular pay.

And that’s when he thought of a guaranteed plan

And the boys in the union backed him co a man.

The boys in the union backed him co a man.

4 . Said Jonathan Tweed, now there's one thing quite queer:

The bosses gee paid every week in the year,

But now when we ask for a guaranteed wage

They rant and they roar and break out in a rage.

Yes, they rant and they roar and break out in a rage.

5. Come all of you workers, pray listen, cake heed,

For this is the message of Jonathan Tweed :

Though big corporations may bellow and rage,

We'll stand up and fight for a guaranteed wage.

Yes, we'll stand up and fight for a guaranteed wage.

"The saddest object in civilization," said Robert Louis Stevenson, "and the greatest confession of its failure, is the man who can work and wants to work, and is not allowed co work." Of course that's not what people who try to sell the nation on so-called "Right-to-Work" Jaws are talking about. They just want to wreck unions. But unions have been concerned for the past century and a half about recurring cycles of panics, booms and depressions chat have plagued our economy. In addition to pushing for full employment legislation, unions have struggled both for unemployment insurance and then for guaranteed annual wages. In 1955, the United Auto Workers carried on a campaign which culminated in a contract with the Ford Motor Company, calling for a form of the guaranteed annual wage, under the term "supplemental unemployment benefits." Soon after, unions in steel, rubber, glass and other industries won similar guarantees in their contracts. Just before the 1955 convention, Ruby McDonald, the talented wife of a Flint auto worker, sent Joe Glazer "a song on the guaranteed annual wage," which he sang to the cheers of 2,500 convention delegates.

ALL TOGETHER

1. No matter your race, no matter your creed,

It's justice for all chat we want and we need,

United in brotherhood, we will succeed

To build our union strong.

CHORUS: All together, all together, we are stronger

every way, AFL-CIO

We will build together, work together for

a better day, AFL and CIO.

2. If you are afraid when your hair's turning gray

They'll open the gates and cast you away,

Then join with your brothers and demand fair play

And build your union strong.

3. Together we'll build and together we'll stand,

Together we'll make this a happier land,

We'll work and we'll sing and we'll march hand in hand

And build our union strong.

This song, celebrating the merger of the American Federation of Labor and the Congress of Industrial Organiations, was written by H. H. Bookbinder, Harry Fleischman and Joe Glazer during the convention sessions. It was sung at the convention by Glazer and symbolized the hopes of many for a new burst of progress by a united labor movement.

TOO OLD TO WORK

Sung by Tommy Makem

1. You work in the factory all of your life,

Try to provide for your kids and your wife.

When you get too old to produce any more,

They hand you your hat and they show you the door.

CHORUS: Too old to work, too old to work,

When you're too old to work and you're too young

co die,

Who will take care of you, how'll you get by,

When you 're too old to work and you're too young

co die.

2. You don't ask for favors when your life is through;

You've got a right to what’s coming to you.

Your boss gets a pension when he is too old;

But you'll get green stamps-you're out in the cold.

3. They put horses to pasture, they feed them on hay;

even machines get retired some day.

The bosses get pensions when their days are through;

Fat pensions for them, brother; nothing for you.

4. There's no easy answer, there's no easy cure;

Dreaming won't change it, that’s one thing for sure;

But fighting together we'll get there some day,

And when we have won we will no longer say:

Walter Reuther once made a speech blasting employers who paid themselves huge pensions and then refused any for their workers. Reuther told of the mine mules that pulled coal cars in his native West Virginia: "During slack times the mules were put out to pasture. They were fed and kept healthy so they would be ready to work when the mine started up again. But did they feed the coal miner and keep him healthy! They did not. And you know why? Because it cost fifty bucks to get another mule, but they could always get another coal miner for nothing." The climax of Reuther's speech was a union pledge to win recognition of the human rights of workers who were "too old to work and too young to die." Reuther's speech and slogan started musical wheels turning in Joe Glazer's head. When the Chrysler workers struck in 1950 for pensions, Glazer finished this song, which helped to maintain union morale during a long, tough strike. The successful strike not only meant $100 a month pensions for the victorious strikers, it also started a wave of such agreements in other industries. And because the union contracts called for reducing managements' costs when government pensions went up, large 'Segments of management joined labor in a drive which added ten million workers to the social security rolls, and brought higher pensions and other benefits to fifty million workers and their families.

AUTOMATION

Sung by Robert Carey

I. I went down, down, down to the factory

Early on a Monday morn.

When I got down to the factory

It was lonely, it was forlorn.

I couldn't find Joe, Jack, John, or Jim;

Nobody could I see.

Nothing but buttons and bells and lights,

All over the factory.

2. I walked, walked, walked into the foreman's shack

To find out what was what.

I looked him in the eye and I said, "What goes? "

This is the answer I got:

His eyes turned red, then green, then blue

And it suddenly dawned on me-

There was a robot right there in the seat

Where the foreman used to be.

3. I walked all around, all round, up and down

And across the factor.

I watched all the buttons and the bells and the lights—

It was a mystery to me

I hollered "Frank, Hank, Ike, Mike, Roy, Ray

Bill and Fred and Pete! " •

And a great big mechanical voice boomed out:

"All your buddies are obsolete."

4. I went home, home, home to my ever-loving wife

And told her 'bout the factory.

She hugged me and she kissed me and she cried a little bit

And she sat down on my knee.

I don't understand all the buttons and the lights

But one thing I will say-

I thank the Lord that love's still made

In the good old-fashioned way.

We are promised chat automation, the "second industrial revolution," will, in the long run, produce higher living standards and greater leisure for the American people. Unfortunately, however, we eat and live in the short run and need food, shelter and clothing in the here and now.

AFL-CIO President George Meany says: "There is no automatic guarantee chat the potential benefits to society will be transformed into reality. While new machines are almost human in the way they solve problems of production, they still cannot create the necessary income to purchase their additional output." Joe Glazer's song, "Automation," which is based on a conversation between officials of the Ford Motor Company and UAW President Walter Reuther, that took place in the first Ford automated plant in Cleveland, is laughing with tears in its eyes. Its lighthearted satire reflects the concern and fear most workers have of the new Age of Automation.

UNION MAID

I. There once was a union maid;

She never was afraid

Of goons and ginks and company finks

And the deputy sheriffs that made the raid.

She went to the union hall

When a meeting it was called,

And when the company boys came 'round

She always stood her ground.

CHORUS: Oh, you can't scare me, I'm sticking to the union.

I'm sticking to the union, I'm sticking to the union.

Oh, you can't scare me, I'm sticking to the union,

I'm sticking to the union till the day I die.

2. This union maid was wise

To the cricks of company spies;

She couldn't be fooled by company stools;

She'd always organize the guys.

She'd always get her way

When she struck for higher pay;

She'd show her card to the company guard

And this is what she'd say:

3. Now you girls who want to be free

Just take a tip from me!

Now get you a man who's a union man

And join the Ladies' Auxiliary.

Married life ain't hard

When you've got a union card.

A union man has a happy life

When he's got a union wife.

As early as 1834, women textile workers in Lowell, Massachusetts struck against wage cuts. Seventy-five years later, 20,000 Jewish and Italian women shirtwaist-makers struck for three months against intolerable New York City sweatshops, pledging themselves to the old Jewish oath: "If I turn traitor to the cause I now pledge, may this hand wither from the arm I now raise." Today, unions like the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America, the International Ladies Garment Workers Union, and the Communications Workers of America have a majority of women members. Millions of other women are unsung heroes of the labor movement, the "union widows"-wives of devoted union leaders who keep their homes and raise their families while their union men organize, negotiate and meet-almost endlessly, it sometimes seems. This song was written by Woody Guthrie in 1940 after a union meeting in Oklahoma City where company toughs failed to intimidate union members or their wives. Millard Lampell supplied the third verse.

The Tarriers include Marshall Brickman,

Clarence Cooper, Eric Weissberg and Robert Carey.

Historical notes written by Harry Fleischman, Director of the

National Labor Service of the American Jewish Committee.