ESCALATION AND CONFRONTATION

Longstanding racial tensions and ongoing resentment about housing and economic discrimination provoked violent confrontations between Black residents and the Detroit Police Department. The number and severity of demonstrations and disturbances increased in the early 1960s, including notable clashes on Belle Isle and Kercheval Street in 1965 and 1966. Witnessing the growing animosity, in the fall of 1966 and spring of 1967 community leaders and the Detroit Commission on Community Relations warned that the city was in danger of experiencing a widespread violent rebellion.

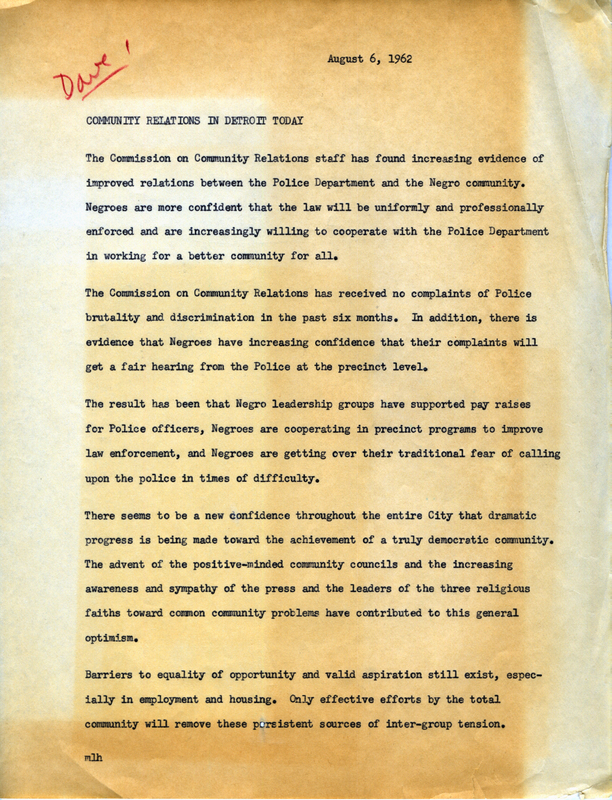

A memo from the Detroit Commission on Community Relations expresses optimism that the relationship between the African American Community and the police are improving. August 6, 1962. Detroit Commission on Community Relations/Human Rights Department Collection, Part 3, Box 65, Folder 13.

A crowd protests the fatal shooting of a Black woman by Detroit Police. July 15, 1963. From the Detroit News Photograph Collection.

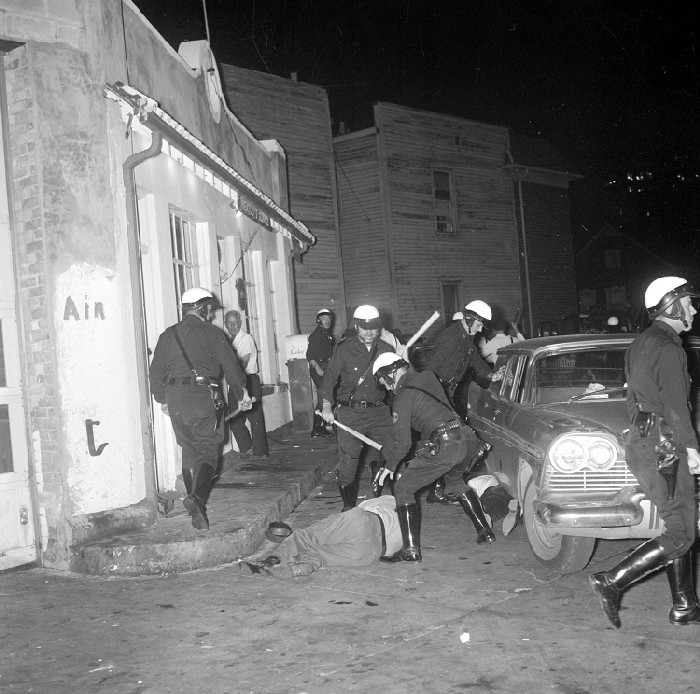

Police outside the Vernor Street Station club a demonstrator protesting the fatal shooting of Kenneth Evans, a white youth. 1963. Photograph from the Detroit News Collection.

A flyer announces a demonstration against instances of police brutality and killings of Black Detroiters. May 15, 1965. Detroit Commission on Community Relations (DCCR)/Human Rights Department Records, Part 1, Series VI, Box 14.

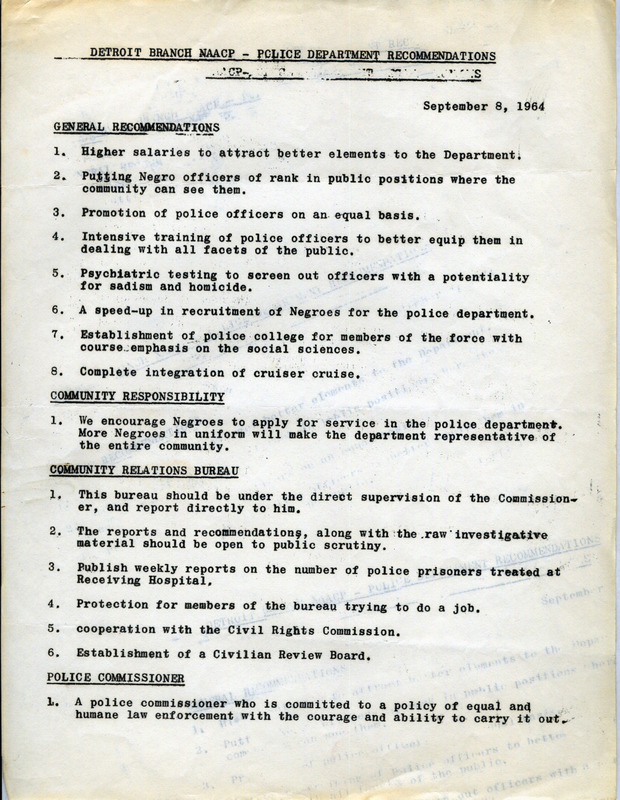

The NAACP Detroit Branch provides recommendations to reduce racial tensions between the Detroit Police Department and Black residents. September 8, 1964. Detroit Commission on Community Relations/Human Rights Department Collection, Part 3, Box 65, Folder 14.

Detroit Police Department Tactical Mobile Unit being dispatched to Belle Isle. July 1, 1965. From the Detroit News Photograph Collection.

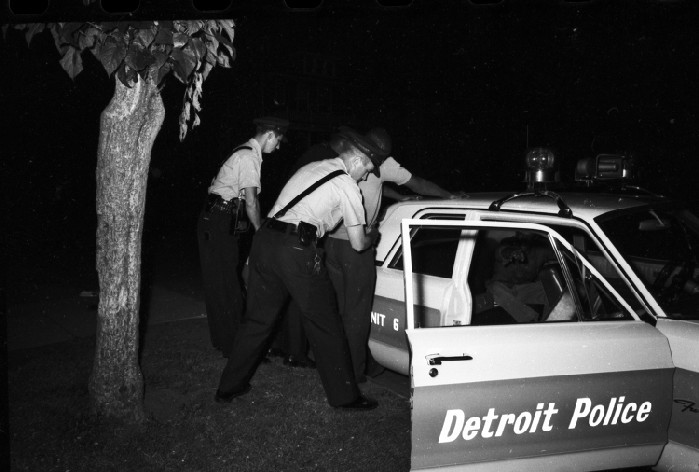

Uniformed police officers "pat down" a man leaned up against a police car at Belle Isle in Detroit, Michigan. Jly 1, 1965. From the Detroit News Photograph Collection.

A memo from the Detroit Commission on Community Relations field staff to James Bush identifies sources of community tension, including, "overcrowded housing, unemployment, parks and picnic areas (informal gatherings), public events (sporting, musical, parades, meetings, forums, demonstrations, etc.), teenagers, police, weather, drinking, escalation of arguments, and/or fights, a combination of any of these." August 18, 1965. Detroit Commission on Community Relations (DCCR)/Human Rights Department Records, Part 3, Box 71.

The Detroit Commission on Community Relations Subcommittee on Police-Community Relations provides an overview of Detroit Police Department recruitment reforms, including "correcting the imbalance of Negro representation on in the department." October 10, 1966. Detroit Commission on Community Relations/Human Rights Department Records, Part 3, Box 68, Folder 20. Click the image to read the full document.

A page from the The Michigan Chronicle, Detroit's major Black newspaper, describes the mood on Kercheval Street following an uprising there. August 20, 1966. Walter P. Reuther Vertical Files Collection, Box 52.

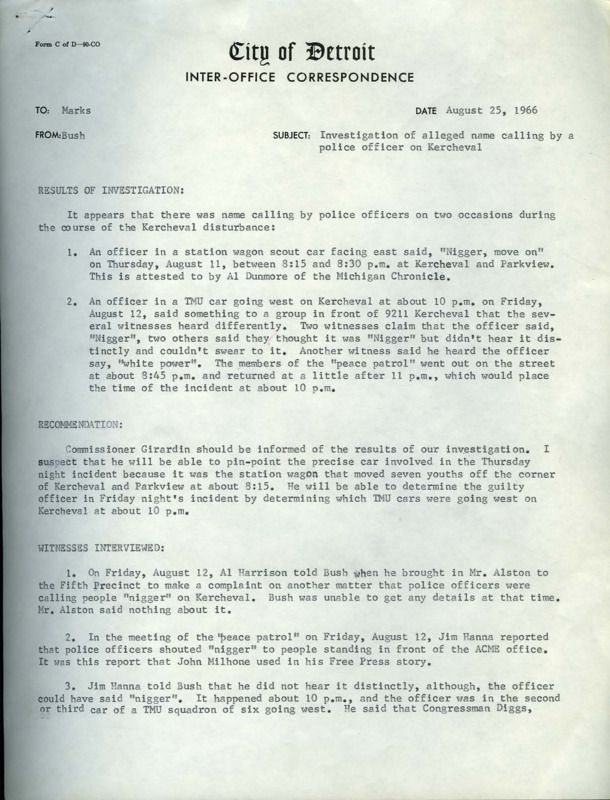

An investigation of Detroit Police officers who reportedly harassed Black youth on Kercheval Street, leading to confrontations between police and Black residents. August 25, 1966. Jerome P. Cavanagh Papers, Box 273, Folder 5.

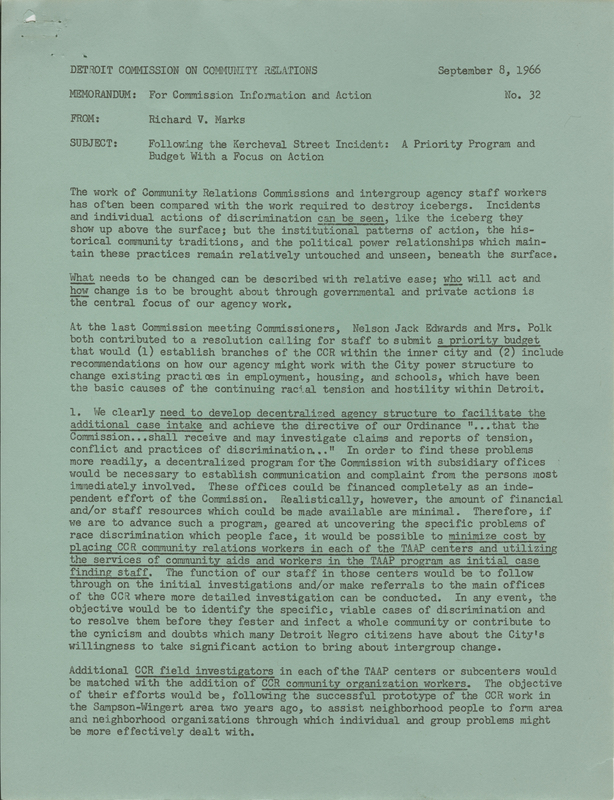

A Detroit Commission on Community Relations proposal for a priority program and budget to effect institutional change within the Commission and the City of Detroit following an August 9, 1966 confrontation between Black residents and police on Kercheval Street. Richard Marks likens the work of the DCCR to destroying iceburgs, explaining that, "Incidents and individual actions of discrimination can be seen, like the iceburg they show up above the surface; but the institutional patterns of action, the historical community traditions, and the political power relationships which maintain these practices remain relatively untouched and unseen, beneath the surface." September 8, 1966. Detroit Commission on Community Relations (DCCR)/Human Rights Department Records, Part 3, Box 71, Folder 9.

What “institutional patterns of action,” “historical community traditions,” and “political power relationships” have you seen in this exhibit that encouraged racial conflict?

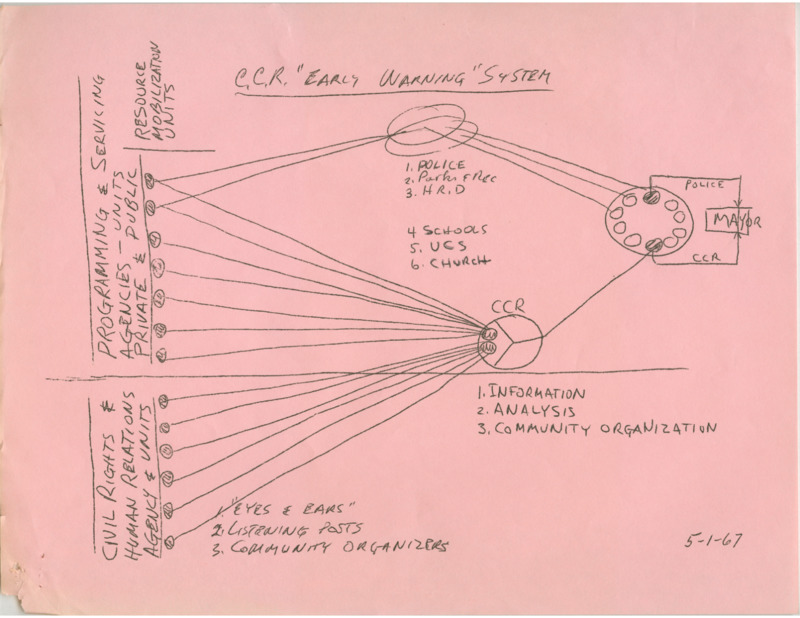

Detroit Commission on Community Relations plans to identify areas of potential civil unrest in the city. May 1, 1967.

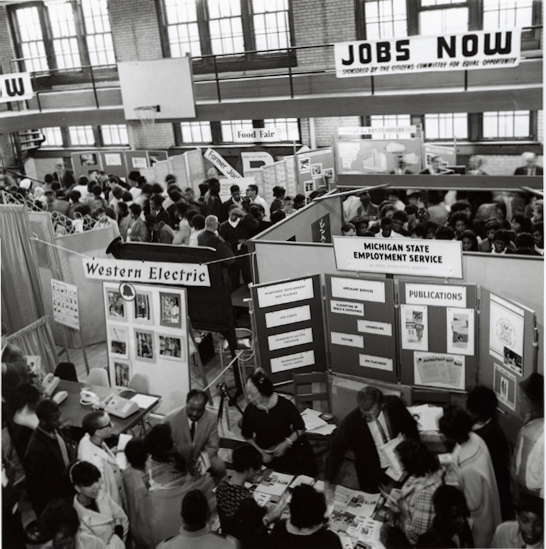

Sponsored by the Citizens Committee for Equal Opportunity and the Virginia Park Citizens Committee, a jobs fair, called the “Jobs Now! Conference,” is held at Hutchins Junior High School, near the place where Detroit’s Civil Unrest will erupt exactly two months later. The jobs fair organizers described the neighborhood as being one of Detroit’s “areas of most critical unemployment.” May 23, 1967. Source: Wayne State University Office of Religious Affairs, Box 18.