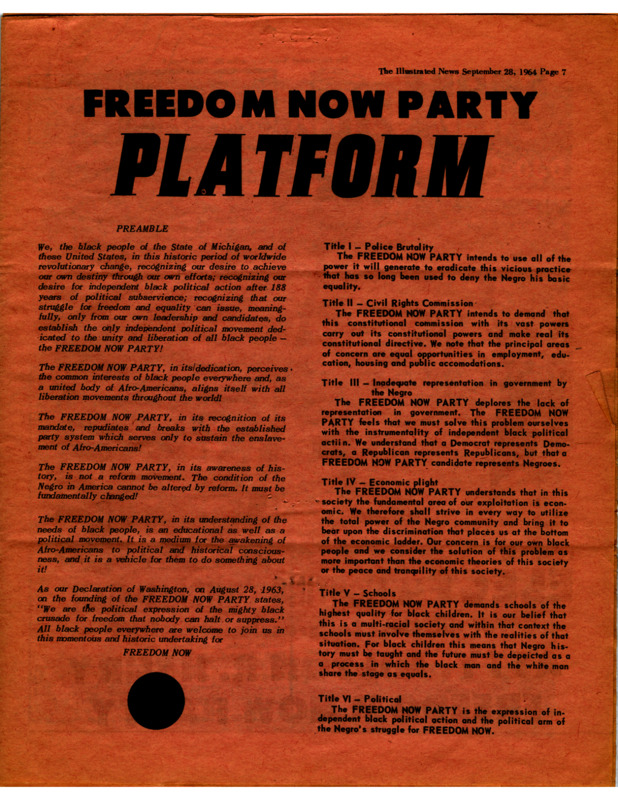

BLACK NATIONALISM

In Detroit, numerous civil rights -- and later, Black nationalist -- organizations had different strategies to empower Black people in the post-World War II era. The Detroit NAACP and Urban League were more mainstream, seeking integration, equal employment, and housing opportunities, and an end to police brutality targeting Black residents. By the early 1960s, these organizations and others pursued increasingly strident forms of protest. They staged mass civil rights demonstrations and school walkouts, hosted public lectures, and formed political parties. Some adopted a Black nationalist ideology centered on self-defense and separatism rather than the non-violence and integration supported by mainstream civil rights groups. Black nationalism also drew inspiration from African independence movements that contributed to an evolving sense of Black pride, unity, and self-determination. The mainstream civil rights movement held sway in cities like Detroit, but Black nationalism influenced their ideas and encouraged more radical perceptions of justice.

Reverend Albert Cleage (later Jaramogi Abebe Agyeman), a prominent Detroit-based activist, exhibited dimensions of Black nationalism through a number of associations. Here, Cleage addresses the audience at Cobo Hall following the “Walk to Freedom” march where Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. gave one of his “I Have a Dream” speeches. From the Detroit News Photograph Collection.

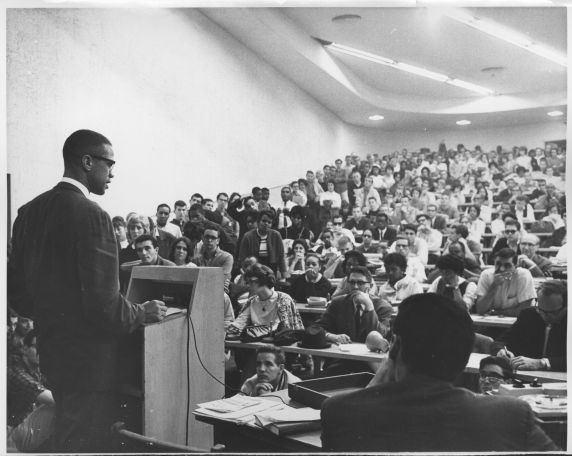

Students listen to Malcolm X speak in Wayne State University’s State Hall in Detroit, Michigan about the Nation of Islam, warning that, “We are not afraid to go to jail or afraid to take the life of those who take our life. We believe in fair exchange. This is the price of freedom, and we are prepared to pay the price.” From the Detroit News Photograph Collection.